Lessons from the Multi-Country Study on Inclusive Education

By Dr. Christopher Johnstone

Lessons from the Multi-Country Study on Inclusive Education

IDP recently wrapped up all reporting and evaluative activities for a Multi-Country Study on Inclusive Education (MCSIE) which ran from August 2019 to October 2024. The study examined three models of USAID-funded early-grade inclusive literacy programs in Cambodia, Malawi, and Nepal. MCSIE sought to derive lessons learned about what works, for whom, and in what context to sustainably advance teaching and learning outcomes for children with disabilities in these specific countries. Readers can access all the study reports on IDP’s MCSIE page. Although we learned several context-specific lessons from the three study countries, we also learned four important lessons about inclusive education that could apply in nearly any setting. We share these below.

Lesson #1: Inclusion is Everyone’s Business

One important lesson we learned from our data is that each project had its own ecosystem for engagement and that engaging all parts of that ecosystem (students, families, teachers, school leaders, national and subnational government / education officials, organizations of persons with disabilities (OPDs), and international development organizations) is essential to ensure inclusion. Some projects focused more on teachers, while others focused more on policymakers, but the best successes came when there was engagement with all these actors. While these actors may have differing views on the best way to support inclusion, and coordination can be a challenge, we learned it is essential to convene and engage with every one of these groups to understand the system in which the project operates. We acknowledge that the more actors involved in a project, the more complicated it becomes. However, once projects end (typically after three or five years), national actors will remain in the country to carry on the good work of inclusion. If donor-funded projects come and go without the engagement of these actors, any impact introduced by projects will likely disappear.

Lesson #2: People are Important, and So are Activities

Lesson #1 helped us understand that engaging with a wide variety of actors is essential to project success. This is because the policies, procedures, and practices that inform inclusive education are ultimately carried out by the actors in the ecosystem. It is essential that donor-funded projects understand and, if appropriate, contribute to policy-level conversations in countries. Similarly, school procedures such as enrollment, national/schoolwide assessment, screening procedures, and personnel decisions impact the likelihood or unlikelihood of effective inclusion. Teacher practice is also critical to inclusive education, as is parent buy-in. Similar to Lesson #1, MCSIE projects either paid a great deal or very little attention to specific policies, procedures, or practices, but we learned that integrating policies, procedures, and practices and committing to the engagement of all actors helped toward creating shared goals for inclusion to enhance its success.

Lesson #3: Rethink “Teacher Training”

A popular and inexpensive model for engaging large numbers of teachers in donor-led projects is through “training.” These events are typically short and involve an expert sharing some form of information in which participants engage. Training dollars are further stretched when the “cascade” method is used and trainees become trainers. We learned from MCSIE that participants enjoyed the trainings provided by USAID programs. Yet, longer-term monitoring and evaluation were needed to understand what type of impact (if any) was made in the classroom after training events. Lessons learned from specific MCSIE countries demonstrated that follow-up engagement like coaching and mentorship, classroom check-ins, and online (i.e., WhatsApp) support groups were effective in helping move brief exposure in training to longer-term teaching changes in the classroom.

Lesson #4: Inclusion is a Comprehensive Process

Finally, in alignment with the lessons learned above, data from the three MCSIE countries indicates that inclusion requires multiple interlocking elements beyond the MCSIE projects’ focal elements. In a forthcoming article, my colleagues and I call this “comprehensive inclusion.” We learned that to actualize inclusion, the following elements must be present in a country:

- National policy advocacy

- School policy advocacy

- National strategic plans

- Inclusive pedagogy

- Elimination of segregation

- Rights-based guarantees

- Strengths-based education models

- Barrier-free schools

- Transition planning

- Inclusive assessment

- Adaptive materials

- Assistive technologies

- Screening and identification

- IEPs

- Family supports

- Accommodations

Addressing these elements may not be feasible within a single project or program. Still, a helpful starting point is for projects to identify contextually relevant touchpoints on which a project can start and further contextually-driven “stretch points” (i.e., working with actors to push inclusion into new areas of the education ecosystem). It takes tremendous work, coordination, contextual understanding, and resources for a program to live up to its billing of being “inclusive.” Still, these ideas may help with starting the process.

Conclusion

Over the last decade, tremendous breakthroughs have been made concerning inclusive education, yet more is needed. The lessons learned from the MCSIE project can help inform donors wishing to engage with inclusive education and demonstrate the commitment level needed to create change in this area. To our partners in the MCSIE countries who are carrying on the excellent work that was started with the projects, we commend you and look for new opportunities to engage in the days ahead.

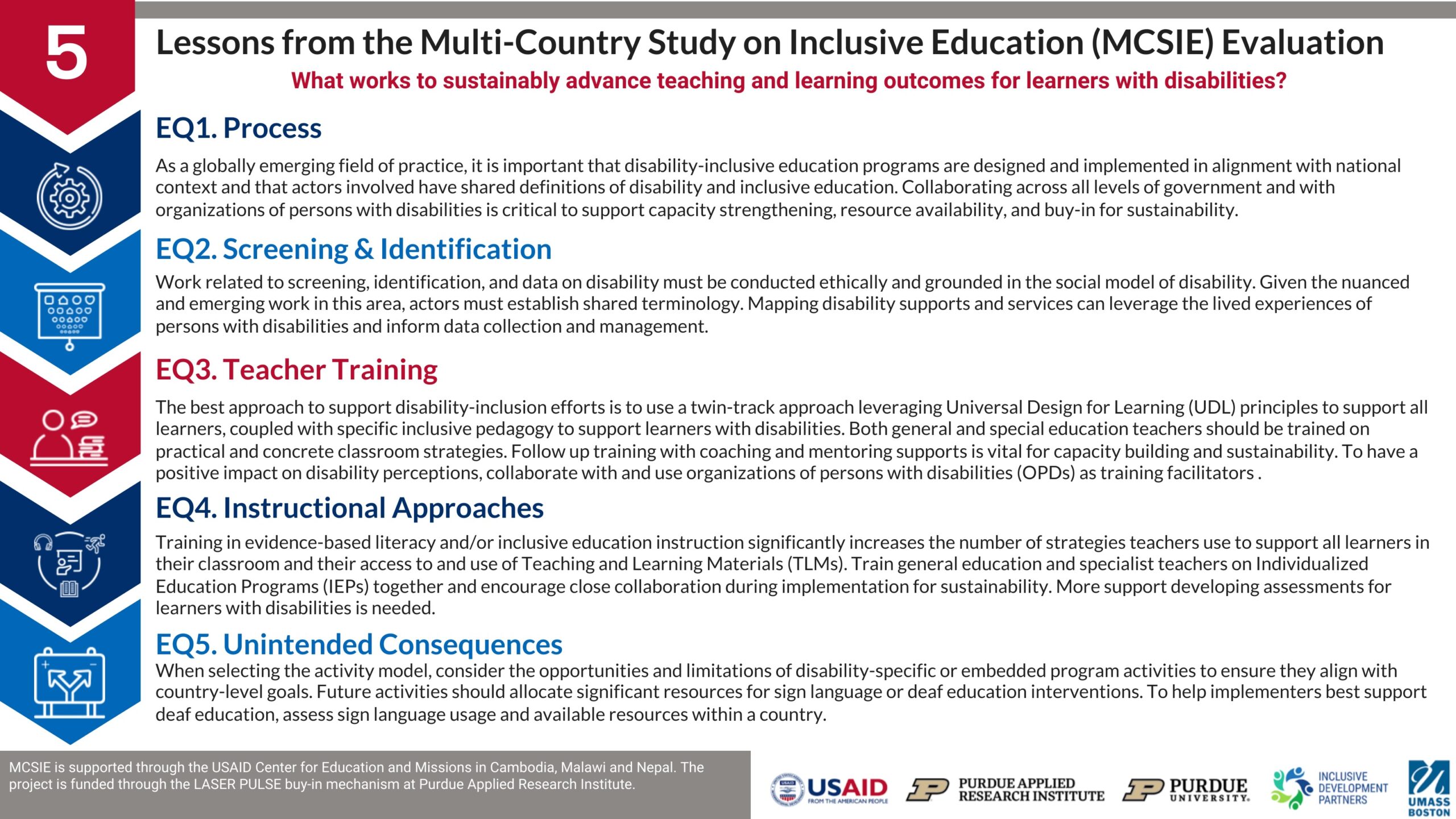

Download the MCSIE Findings graphic, which summarizes the lessons learned on what works in teaching and learner outcomes for learners with disabilities across the evaluation questions.