An Evaluator’s Reflection: Insights from the Multi-Country Study on Inclusive Education (MCSIE)

By Dr. Christopher Johnstone

From 2019 – 2024, IDP led the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded Multi-Country Study on Inclusive Education (MCSIE). The MCSIE study assessed the effectiveness, relevance, and impact of three USAID-funded early-grade literacy inclusive education activities in Cambodia, Malawi, and Nepal. This study brought together over 60 international and local experts with experience in research and evaluation of disability, inclusive education, and systems change. My role focused on one country, and I was just one member of the large team dedicated to learning all we could from the experiences in the three countries. While each activity was called an inclusive education program, each had a very different approach to implementation. Each project also had the extreme challenge of working through the COVID-19 pandemic. As we close out the MCSIE study, I asked my colleagues what they learned from this large and very complex project so we may share it with others who endeavor to support the progressive realization of inclusive education globally. Here’s a summary of what they said.

Definitions Matter

Inclusive education is a concept that has been around for decades. However, its conceptualization is still very much “in progress,” and how it is conceptualized and enacted varies from country to country (see Box 1). Because of this, donor-funded activities need to be very clear on terminology and scope of what is considered inclusive. In this study, we learned of the complexities of what was considered inclusive and what was not. There were differences in understanding and conceptualization of “inclusive” among donors, implementing partners, national constituents, and evaluators. There were differences in conceptualizations, and the evaluation work was conducted in seven languages (Cambodian Sign Language, Chichewa, English, Khmer, Malawian Sign Language, Nepali, and Nepali Sign Language). Although expert translators and interpreters supported the work, nuances and misunderstandings occurred in such complex communicative environments (see Box 2). Conceptualization and cross-language conceptualization were critical to understanding how inclusive education was evolving in specific contexts and across contexts. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was a helpful guide for creating a shared definition. Still, it was also critical that the evaluation captured nuanced definitions and understandings of inclusion within specific national contexts and program designs to inform the broader evaluation.

Box 1

“There is no unified definition of inclusive education at USAID and projects can define it differently.”

Box 2

“Don’t underestimate the importance of good translation, especially when it comes to evaluating conceptual understandings of key terms such as disability or inclusive education.”

Holistic Stories Matter

Inclusive education is widely accepted as a process, not a specific intervention. The CRPD calls this process the “progressive realization” of inclusive education, meaning it is an ongoing renewal of policies and practices to serve diverse learners better. An essential lesson from MCSIE was that multiple qualitative and quantitative data points allow for a holistic view of inclusive education. In another blog I wrote for IDP, I suggested that inclusive education is driven by an ecosystem of actors such as ministry officials, local government officials, school administrators, teachers, parents, and learners. It was important for partners to track learner outcomes of literacy interventions for this evaluation because such outcomes were the focus of the projects. Still, it was also critical to understand how actors conceptualized and advocated for inclusion within broader educational systems. Inclusive education is about teaching strategies, but it is also about strong policies, supportive community environments, and fighting discrimination. Because MCSIE had so many different forms of data [1], reports could tell holistic stories of the “progressive realization” of inclusive education in single and across settings. These reports could also tell a holistic story of what appeared promising and what practices might be reconsidered in future projects. Such holistic data collection would not have been possible if the MCSIE project was under-funded. Thankfully, an adequate budget was in place that allowed for multi-level, multi-method data collection.

Representation Matters

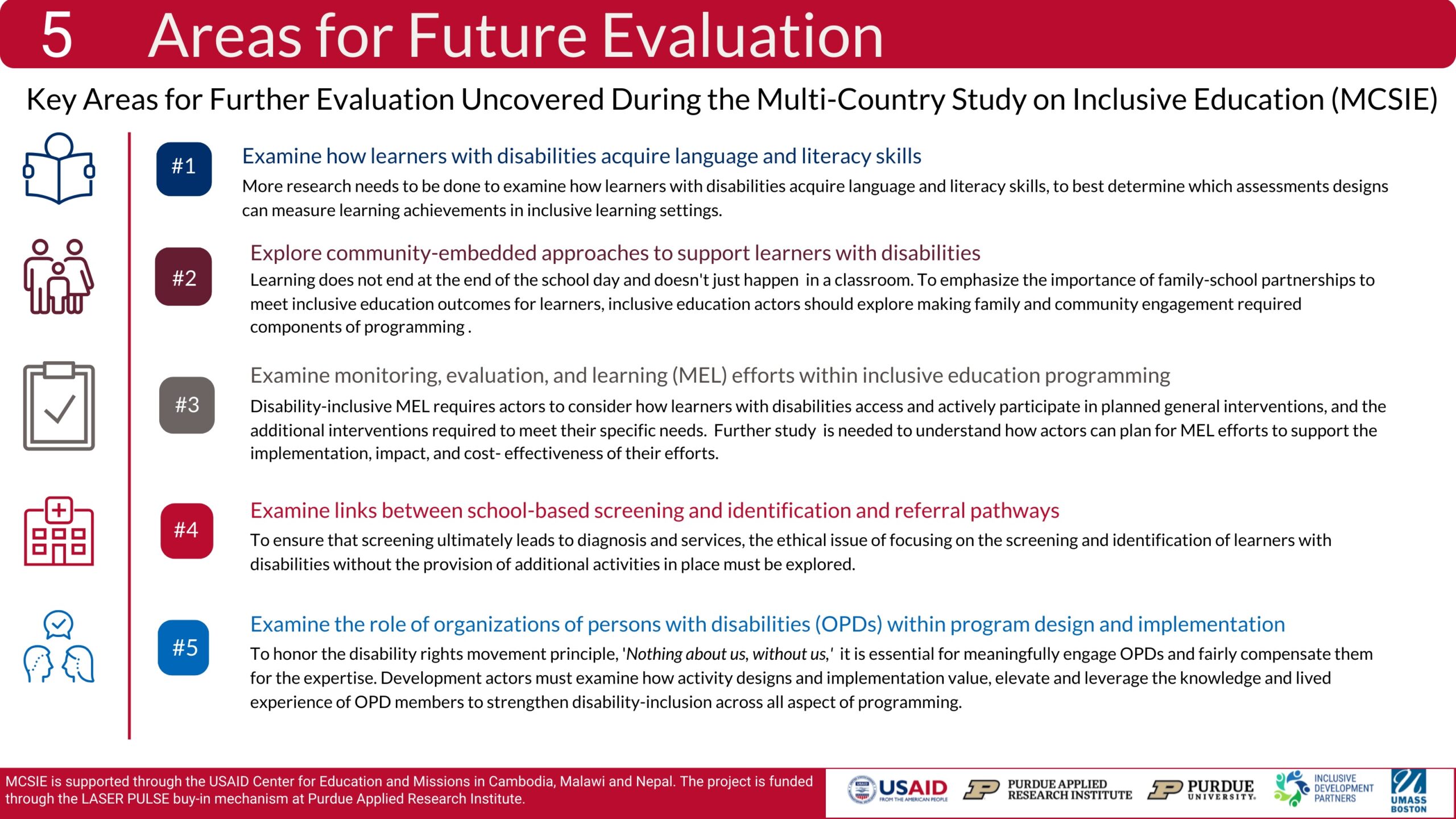

A third important lesson learned from the evaluation was that Organizations of Persons with Disabilities(OPDs) were critical partners in the evaluation. It goes without saying that all evaluations that engage with disability should have a “Nothing About Us, Without Us” focus and that OPDs provide a structured way of enhancing disability representation in donor-funded activities. However, OPD presence in MCSIE was felt in multiple streams of evaluation work. As an evaluation, IDP focused on hiring individuals with disabilities in Nepal and partnered with the Cambodian Disabled Peoples Organization (CDPO) to complete data collection and interpretation and help navigate and map the current disability and education systems in each country. [2] The projects evaluated in Malawi and Nepal also engaged OPDs in their implementation to varying degrees. Three things were clear from these examples. First, partnerships with OPDs helped break down negative perceptions of disabilities among stakeholders. Second, their engagement in large projects helped raise the reputation of these organizations in their national and sub-national governments. Third, their perspective was invaluable for contextualizing and informing MCSIE findings due to their lived experience, technical expertise, and understanding of local systems, cultures, and norms. OPDs are not the only pathway for disability representation in evaluations but provide an essential point of contact for future disability-inclusive donor-funded activity.

Concluding Thoughts

Investing in disability-inclusive programming and evaluation is vital to creating more equitable and just societies. USAID and other donors have philosophically committed to inclusive education and have put resources behind these commitments. Evaluations help donors and implementers understand the best way to do the work. At the start of the MCSIE study, the inclusive education activities in the three countries were USAID’s most concerted efforts to date to build systems to support learners with disabilities. Studying them as comparative and complementary data points was very helpful in understanding global directions for inclusive education. Large, multi-country evaluations can be complex but are worth the investment, and the MCSIE evaluation seems to have paid dividends. Although not every moment of this evaluation was perfectly orchestrated – it could not be because of the COVID-19 pandemic – many vital lessons were learned.

Inclusive education can occur as a project within education systems, or inclusion can define how a system operates. A holistic, multi-pronged approach to understanding these distinctions is warranted. There will always be specific interventions to assess in education programming. Still, MCSIE demonstrated that donors and governments also need to understand how policy, resourcing, the organizational culture of schools, and parents’ access to services also inform inclusive education. It is also critical to know what exactly “inclusive education” means for different actors – in different languages – to understand why particular approaches are undertaken and why some innovations may never get off the ground. These holistic understandings and evaluations are well-served in large projects by knowledgeable partners, including OPDs, who can inform and interpret how inclusive education takes shape in particular contexts and across contexts.

End Notes

[1] MCSIE conducted focus groups (n= 949 participants), classroom observations (n =443), training observations (n = 29), training pre/post surveys (n=470), teacher surveys (n=434), household surveys (Cambodia and Nepal [n=243]), and implementing partner surveys (n=165). Over 800 secondary data sources were reviewed, including activity documentation and datasets, national policies and laws, and secondary source documentation comprised of presentations, activity and donor-funded reports, and academic literature.

[2] IDP sought to hire local persons with disabilities or OPD partners in Malawi, however was unable to do so because of project needs and conflicts of interest due being part of the activity being evaluated in Malawi.