Are disability labels needed before teachers can support children to learn? Results of discussions from a Soma Umenye workshop on Universal Design for Learning.

Anne Hayes (IDP), Hayley Niad (IDP), Kate Brolley (Chemonics International)

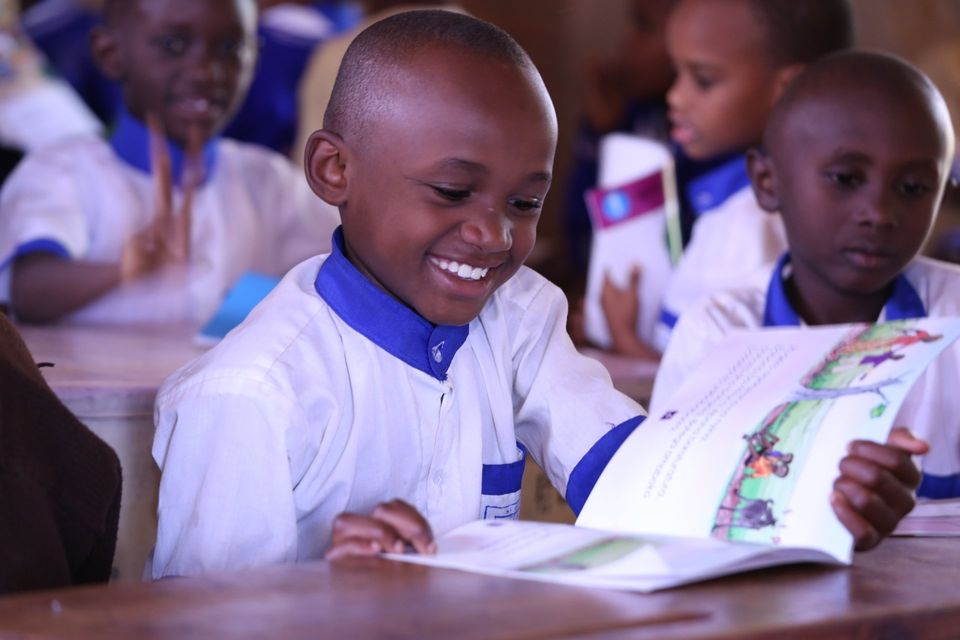

In late November/early December of 2019, USAID Soma Umenye and Inclusive Development Partners (IDP) held a workshop in Rwanda with key education stakeholders including representatives from the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC), the Rwanda Education Board (REB), University of Rwanda College of Education, teachers, district supervisors, and Kinyarwanda specialists to co-develop a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework for Rwanda in support of the country’s goal to strengthen quality inclusive education. REB and Soma Umenye are piloting a UDL approach to Kinyarwanda instruction throughout the 2020 schoolyear, providing training and support to 25 schools (P1 teachers and head teachers) in Gicumbi District. The pilot builds off an existing research base that affirms the benefits of using UDL strategies to support struggling learners, in addition to being developed in close collaboration with key stakeholders according to the strengths and needs of the Rwandan context. This workshop resulted in toolkit to supplement the existing P1 teacher’s guide and a training module for pilot teachers, head teachers, and sector/district education officials.

One of the discussions that dominated a few days of the workshop was the debate related to the need to identify students with a particular disability before teachers are able to provide them with effective classroom supports. This discussion highlights an interesting debate that is taking place in other countries all over the world. This debate is even more relevant in low-resource settings that may lack the resources required to provide accurate diagnosis, and where policy-makers struggle to determine the best use of the often limited finances they have for inclusive education.

So, do you need to identify a child as having a particular type of disability before you can support a child in the classroom?

The simple answer is no. This is because all children are individuals. Though students with disabilities may share many similarities with other students who have the same disability label, each individual will have different academic strengths, needs and be motivated to learn in different ways. In the classroom, it is more important to know what a particular child needs to be successful and often a disability label is insufficient in providing an academic roadmap.

Knowing which students are struggling in the classroom, however, is extremely important as this this knowledge is often paramount to a student’s academic success. But students may struggle to learn for many different reasons including, but not limited to, hunger, recurring illnesses, language differences, or exposure to violence. In fact, these other factors may be more of a barrier to education than a student’s disability. Also, it is extremely important that all students receive universal and regular vision and hearing screenings, as this knowledge is needed for referral to basic health services, and can also help teachers to modify the classroom environment to support students with vision or hearing challenges. Knowing which students need additional supports and knowing which students may have vision and hearing challenges is different than labeling students with various diagnosis such as autism versus intellectual disability, dyslexia versus dysgraphia, etc. What is more important is that teachers design an instructional environment which responds to children’s known strengths and areas of need. Irrespective of whether students have had a proper diagnosis of disability, a teacher who uses instructional methods to cater to various learning needs will be to facilitate the most essential building blocks of inclusive education.

This was a topic that was discussed at great length amongst the Rwanda workshop participants. In the end, it was agreed that it is more important to have an instructional approach, such as UDL, that meets that needs of all students versus placing an overemphasis on the need to identify or label a student’s disability. The Rwandan team also felt this was more realistic in Rwanda as not only is there a lack of identification services but also teachers with large class sizes might have difficulty adapting their instruction for particular students with particular disabilities. Instead, promoting a more inclusive approach, with low-cost and replicable teaching strategies, that serves all learners would be more realistic. Soma Umenye and IDP will pilot this approach within this research project and then based on the results assess how UDL could be best applied in educational contexts such as Rwanda.